Hitting Baseballs and Blocking Swords

###Learning to Fight

When I was an undergraduate student, I used to fight with the Society of Creative Anachronism (SCA). I remember when I was first learning how to strike with a rattan sword, my teacher told me that ideally, I should not hit my target with the tip of the sword, but rather about 1/3 of the way down. I didn’t think too much about this at the time; later I learned that baseball coaches often tell their players the exact same thing. You want to try to hit a baseball about 1/3 of the way down the bat. This was too much of a coincidence for me. Why is that the case?

###Setting up the Free Body Diagram

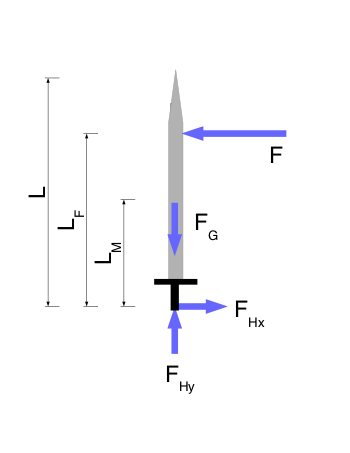

Take a look at the free body diagram of a sword below. Assume that the sword has a total length of \(L\) and some mass \(M\). In this simple problem, we will assume that the center of gravity and center of mass lie on the same point a distance \(L_M\) from the bottom. The weight of the sword is \(F_G\).

The fighter strikes or blocks another object at a distance of \(L_F\) from the bottom of the sword. The force of the strike is \(F\).

The fighter holds the sword at one end, exerting forces \(F_{Hx}\) and \(F_{Hy}\). The “H” signifies the force due to the fighter’s hands.

This is a two-dimensional problem involving the dynamics of a rigid body.

###Solving the Free Body Diagram

To solve this problem, we can sum the forces and the torques in the system.

The forces in the y-direction must sum to zero if we want to keep the sword upright. We know that \(\vec{F}_G = -Mg\hat{y}\). Thus:

\[\begin{equation} \sum F_y = 0 \Rightarrow \end{equation}\] \[\begin{align} \vec{F}_{Hy} + \vec{F}_G &= 0 \\[0.1cm] F_{Hy} - Mg &= 0 \\[0.1cm] F_{Hy} &= Mg \\[0.1cm] \end{align}\]Since we assume that the incident force \(F\) is directed entirely in the \(\hat{x}\)-direction, this just means that we need to exert a force equal to the weight of the sword to keep it level.

The sum of the forces in the \(\hat{x}\)-direction is given by:

\[\begin{equation} \sum F_x = ma_x \Rightarrow \end{equation}\] \[\begin{equation} \vec{F}_{Hx} + \vec{F} = M \vec{a}_G \end{equation}\] \[\begin{equation} \vec{a}_G = \frac{\vec{F}_{Hx} + \vec{F}}{M} \end{equation}\]Here, \(\vec{a_G}\) is the acceleration of the sword at its center of gravity. In order to solve this expression further, we need to look at the torques on the sword. We will take our pivot to be the point where the fighter holds the sword. Then, the sum of the torques is equal to the moment of inertia of the sword multiplied by its angular acceleration:

\[\begin{equation} \sum \tau = I \alpha \end{equation}\] \[\begin{align} F L_F &= I \alpha \\[0.1cm] &= I \frac{a_G}{L_G} \end{align}\]As we see above, we can replace the angular acceleration of the sword by the linear acceleration of the center of mass of the sword.

For now, let’s assume that the sword can be approximated as a stick with uniform mass density in order to calculate the moment of inertia. Obviously, if you want to do a more realistic calculation, you should carefully calculate the value for I. Using the parallel axis theorem:

\[\begin{align} F L_F &= I \frac{a_G}{L_G} \\[0.1cm] &= \left ( \frac{1}{12}ML^2 + ML_G^2 \right )\frac{a_G}{L_G} \\[0.1cm] &= \left ( \frac{1}{12}ML^2 + ML_G^2 \right ) \frac{1}{L_G}\frac{|\vec{F}_{Hx} + \vec{F}|}{M} \end{align}\]Now, in the best case scenario, you would feel no recoil on the sword when you strike or block. Thus, we will set \(\vec{F}_{Hx} = 0\):

\[\begin{equation} F L_F = \left ( \frac{1}{12}ML^2 + ML_G^2\right ) \frac{1}{L_G}\frac{F}{M} \end{equation}\] \[\begin{align} L_F &= \left ( \frac{1}{12} \frac{L^2}{L_G} + L_G \right ) \\[0.1cm] &= \frac{L^2 + 12L_G^2}{12L_G} \\[0.1cm] \end{align}\]So here we have it! The value \(L_F\) is the “sweet spot” that we are looking for. If the fighter manages to aim the input force at some distance \(L_F\) from the bottom of the sword, she theoretically feel no force on her hands; she can keep swinging. If she is slightly above or below this point, she will feel a balancing force either forward or backwards.

Let’s look at the case where the center of mass (\(L_G\)) is exactly halfway up the length of the sword (\(L\)):

\[\begin{align} L_F &= \frac{L^2 + 12L_G^2}{12L_G} \\[0.1cm] &= \frac{L^2 + 12 \left ( \frac{L}{2} \right )^2}{12 \left ( \frac{L}{2} \right )} \\[0.1cm] &= \frac{4L^2}{6L} \\[0.1cm] &= \frac{2}{3}L \end{align}\]As we see, the sweet spot is 1/3 of the way from the top of the bat (2/3 of the way from the bottom).