Zooming in on the Magnifying Glass

Introduction

You have probably played around with a magnifying glass at some point in your life. You can zoom in on small objects, focus light to a point, and make hilarious faces. Many introductory physics classes analyze the simple magnifier (i.e. the magnifying lens), but a lot of the details of the derivation are glossed over. This leads to equations that seem to magically come out of thin air.

Let’s take a close look at the simple magnifier and your eyeball.

The Near Point

Your eye is an amazing organ that detects light rays and converts their pattern to electro-chemical impulses. An in-depth summary of the mechanisms of the eye would take weeks to cover. Right now, we are simply interested in the optical resolution of your eyeball.

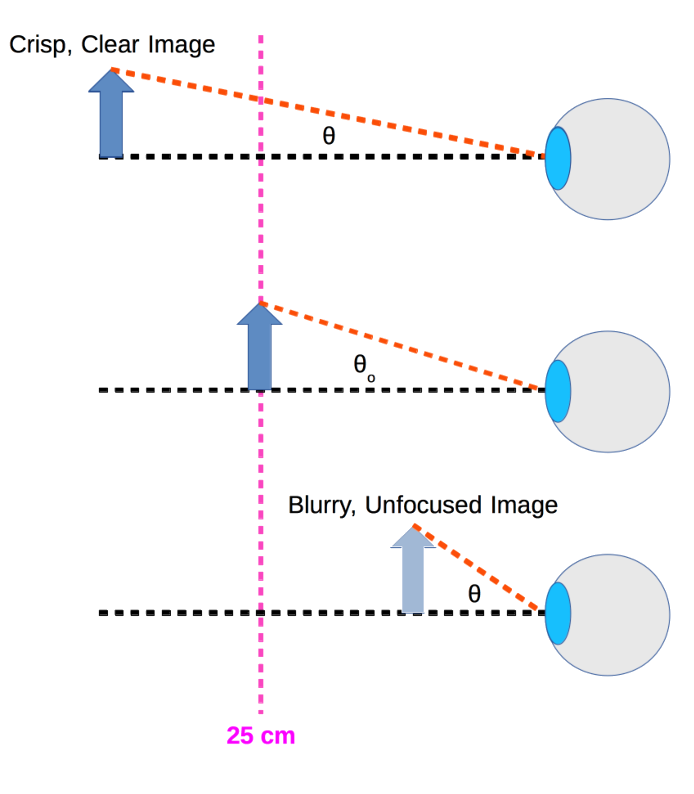

Consider the diagram above. When an object is far away from your eye, you can see it very clearly (even though it appears small). As it moves closer and closer to your eye, it seems to get bigger and bigger - it’s angular magnification is increasing. It is easy to distinguish little details on the object as it approaches your eyeball. However, there comes a point past which the object looks blurry and unfocused; we call this the near point of your eye. For a relaxed eyeball, this point is about 25 cm away.

The angular magnification of the eyeball system is defined as:

\[\begin{equation} m = \frac{\theta}{\theta_o} \end{equation}\]where \(\theta\) and \(\theta_o\) are shown in the diagram above. We use the near-point of the eye as the baseline for angular magnification. Thus, as the object gets closer to your eyeball, its angular magnification increases (making it look bigger). Once the object passes the near point of your eye, you cannot focus on it properly. Thus, there is an upper limit to the angular magnification of your eye.

Linear Magnification

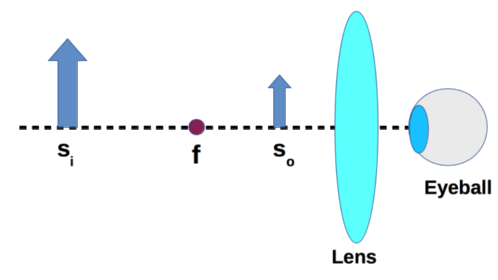

This is where the magnifying glass comes in. Let’s analyze the simple magnifier (i.e. a single converging lens) in the diagram below. Notice that we put the lens between the object and your eyeball. Additionally, the object distance is smaller than the focal length. Although you may not realize this, you naturally find this position when you focus on an object with a magnifying glass.

We will say that the focal length of the lens is equal to \(f\) and the object distance is equal to \(s_o\). We can solve for the image distance (\(s_i\)):

\[\begin{equation} \frac{1}{f} = \frac{1}{s_o} + \frac{1}{s_i} \end{equation}\] \[\begin{equation} \frac{1}{s_i} = \frac{1}{f} - \frac{1}{s_o} = \frac{s_o - f}{s_o f} \end{equation}\] \[\begin{equation} s_i = \frac{s_o f}{s_o - f} \end{equation}\]We can use the expression for image distance to find the linear magnification. Remember that the linear magnification is the negative ratio between image and object distance.

\[\begin{align} M &= -\frac{s_i}{s_o}\\[0.1cm] &= -\frac{\frac{s_o f}{s_o - f}}{s_o}\\[0.1cm] &= \frac{f}{f - s_o} \end{align}\]Notice that the magnitude of the linear magnification is always greater than one because \(f\) is positive and \(f \ge s_o > 0\).

Angular Magnification

Now that we have an expression for the linear magnification, we can use it to derive the expression for angular magnification. Recall from above that the angular magnification is simply the ratio of the angles \(\theta\) and \(\theta_o\):

\[\begin{equation} m = \frac{\theta}{\theta_o} \end{equation}\]We are going to use the small angle approximation to solve for \(\theta\) and \(\theta_o\) which states that for small angles:

\[\begin{equation} tan\theta \approx \theta \end{equation}\]It is straightforward to find the angle \(\theta_o\). Remember, by definition \(\theta_o\) describes the object when it is placed at the near point. If the object has a height \(h\):

\[\begin{equation} tan\theta_o = \frac{h}{25 cm} \approx \theta_o \end{equation}\]Solving for \(\theta\) is a bit trickier. We know that the image distance, and thus the angle \(\theta\), changes as a function of object distance and focal length. The final expression for \(\theta\) could be rather complicated, depending on the properties of the eye and the lens. Instead of dealing with the complicated math, let’s focus on the case when the eye is completely relaxed and the image is located infinitely far away. This occurs when the object distance \(s_o\) is equal to the focal length \(f\) of the lens.

On first glance, this might seem like a problem - the linear magnification is infinitely large:

\[\begin{equation} M = \frac{f}{f - s_o} = \frac{f}{f - f} = \frac{f}{0} = \infty \end{equation}\]However, the angle \(\theta\) is finite:

\[\begin{equation} tan\theta = \frac{h}{f} \approx \theta \end{equation}\]Now, we can solve for the angular magnification:

\[\begin{align} m &= \frac{\theta}{\theta_o}\\[0.1cm] &= \left ( \frac{h}{f} \right ) \left ( \frac{25 cm}{h} \right )\\[0.1cm] &= \frac{25 cm}{f} \end{align}\]Conclusion

It’s a bit weird, isn’t it? We solve for the angular magnification of the simple magnifier by projecting the image to infinite distance. But as weird as it sounds, your relaxed eye is good at resolving images that are very far away. Now of course, we use infinity just to make the math easier - it is an idealistic approximation. However, even though it is an approximation, it still yields a very accurate result.